We have been sold an illusion: that we can approach product work with clinical neutrality. That if we gather the right data, apply the right frameworks, and follow a logical process, we can arrive at the “objective” decision.

It sounds reassuring. It also happens to be false.

Every product decision you make, from which customer segment to prioritize, to how you word a piece of product copy, to whether you delay a launch for quality, carries the imprint of your values, your experiences, your fears, and your worldview.

There is no neutral PM. And pretending there is one is dangerous.

When I mentor PMs, I often hear this phrase: “I just want to make the data-driven choice.”

That instinct comes from a good place. We’re trained to minimize personal bias and to believe that if the numbers back us up, our decision must be fair and correct.

But data doesn’t speak for itself. Data is collected, framed, and interpreted by humans and those humans bring their own lenses.

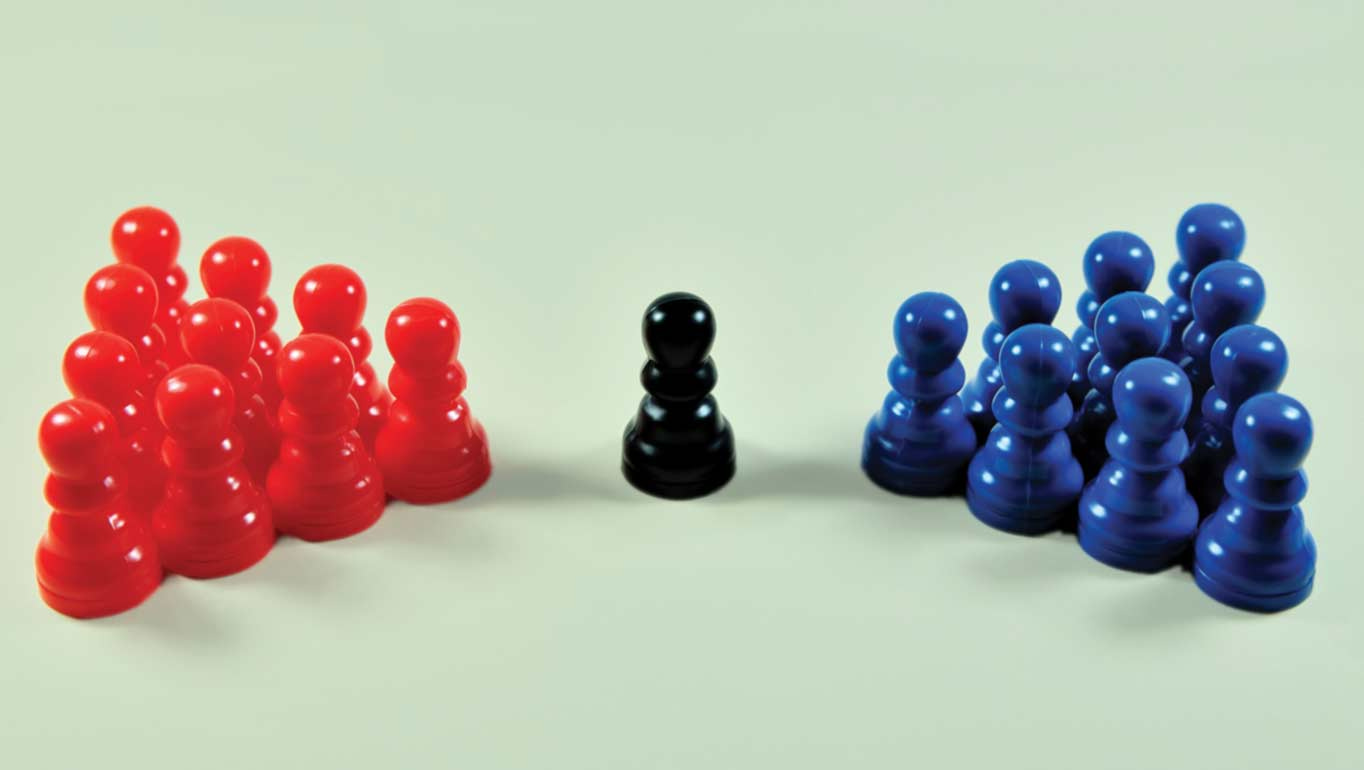

Consider a camera lens. Two photographers can stand in the same spot, point their cameras at the same subject, and capture very different images depending on focal length, aperture, and framing. The raw scene hasn’t changed. The lens has.

Product is no different. You and I can look at the same dataset and walk away with opposite conclusions because what we notice, what we ignore, and what we weigh heavily are all shaped by our lenses.

The Bias in Every Choice

If I am being honest, Bias isn’t always a dirty word. It simply means leaning in a particular direction. Every PM leans. The problem is when you’re unaware of your lean.

Let’s take a few examples.

1. Prioritization

You’re looking at a list of potential features. One helps enterprise customers. Another helps small businesses. Both align with company goals. Which do you pick?

If you grew up working in startups, you might feel a pull toward SMBs, they remind you of scrappy builders. If you’ve spent time with enterprise sales teams, you might instinctively see the enterprise path as more viable. That’s bias.

2. Trade-offs

Do you delay launch to polish quality, or ship fast and fix later?

If you once had a painful miss due to a buggy launch, you’ll likely bias toward caution. If you’ve seen momentum die from over-polishing, you’ll bias toward speed. Neither is objectively right or wrong. But both are value-laden.

3. Metrics

Do you measure success by revenue, engagement, or satisfaction?

Your choice reflects what you and your company value. Optimizing for one often comes at the expense of another. Pick revenue, and you may sacrifice delight. Pick engagement, and you may sacrifice trust. There is no neutral ground.

So if neutrality is impossible, why do we cling to the myth?

Three reasons:

Cover. Claiming “the data told us” shields us from accountability. If things go wrong, we can say, “Don’t blame me, blame the numbers.”

Comfort. Neutrality feels safer. It pretends decisions are straightforward, not messy, not political.

Culture. Many organizations reward the appearance of objectivity. A PM who says, “I followed the framework,” is less threatening than one who says, “This reflects my values.”

But the cost of this myth is high. It blinds us to the ways our choices are shaped by hidden biases. And it prevents us from being honest leaders.

The truth is, product work is a mirror. The decisions we make reflect not just the company’s goals but also our personal values.

Are you optimizing for the loudest voices in the room, or for the long-term health of your customer base? That’s a reflection of what you fear and what you prioritize.

Are you pushing for features that benefit underserved groups, even if the business case is shaky? That’s a reflection of your empathy and worldview.

You can’t remove yourself from the work. The product is you.

What To Do Instead

If neutrality is a myth, what should PMs do?

The answer is not to lean harder on frameworks or pile on more metrics. It’s to make your biases explicit, test them, and hold them accountable.

1. Name Your Lens

Before you argue for a decision, say out loud: “I’m biased toward X because of my experience with Y.”

For example: “I tend to push for quality because I’ve seen what happens when users lose trust.”

This doesn’t invalidate your argument. It makes it more trustworthy.

2. Expose Trade-offs

Don’t let a decision hide under a blanket of “the data says.” Force yourself and your team to articulate: “If we do this, who benefits? Who pays the cost?”

Amazon does this relentlessly with their “working backwards” process, explicitly writing down who the customer is, what they gain, and what trade-offs are being made.

3. Diversify Your Inputs

Bias narrows your field of vision. Countering it requires two things working together:

Internal reflection — pausing to surface the assumptions you’re bringing into the decision.

External input — deliberately seeking out perspectives you don’t naturally hold.

Start with a short reflection loop before big calls:

What am I assuming about the customer, and why do I believe it?

How much of that belief comes from past scars or personal experience, rather than fresh evidence?

Who might experience this product differently than I do?

Then pressure-test those reflections with external voices. That could mean user researchers, customer support teams, or even a quick advisory session with customers outside your “core segment.”

Reflection forces you to admit where your lens is tilted; external input helps you correct the tilt. Neither is enough alone.

4. Stress-Test with “What If”

Ask: “What if my assumption is wrong? What if the opposite were true?”

Netflix used this thinking when it pivoted from DVDs to streaming. Their bias had always been toward logistics and distribution. By asking “what if our users don’t want physical media at all?” they broke their own frame.

5. Anchor in Principles

Frameworks can shift. Metrics can shift. But values should be steady. Decide as a product manager and as a company what principles guide you when the data is ambiguous.

Apple anchors on privacy as a principle. That’s why they roll out privacy-preserving defaults even when advertisers and short-term revenue push the other way.

The Courage to Own It

At its core, rejecting neutrality takes courage.

It means saying: “This is the decision we made, these are the values it reflects, and these are the trade-offs we accept.”

That’s scarier than saying, “The framework told us so.” But it’s also far more honest.

Customers respect honesty. Teams respect honesty. Leaders respect honesty.

And if you want to build products that matter, honesty is your real leverage.

Here’s the irony: the PM who admits their bias, owns their values, and makes the trade-offs explicit ends up being more trusted than the PM who pretends to be neutral.

Neutrality looks safe. But it actually undermines trust. People see through it.

Owning your values looks risky. But it builds credibility. People follow leaders who are clear about what they stand for.

I am curious;

What’s one product decision you’ve made recently where you noticed your personal experience shaping the outcome?

Have you ever disagreed with a team because their bias clashed with yours and how did you resolve it?

I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments.

👏👏👏👏👏